|

|

| Line 31: |

Line 31: |

| Over time, different tribes would put them to different uses, some keeping them as simple livestock while others built nomadic lifestyles around their ability to pack hundreds of pounds of supplies over anything but desert terrain; many, such as the [[Iwu Gioki]], would incorporate them as religious sacrifices, practices that continue in the modern day. | | Over time, different tribes would put them to different uses, some keeping them as simple livestock while others built nomadic lifestyles around their ability to pack hundreds of pounds of supplies over anything but desert terrain; many, such as the [[Iwu Gioki]], would incorporate them as religious sacrifices, practices that continue in the modern day. |

|

| |

|

| | [[File:HistyaGrazing.jpg|left|thumb|250px|A herd of Histyas grazing in the forests of Kamuekiko.]] |

| The arrival of colonists from other worlds would further complicate matters, as the settling [[starwars:Human|Human]] and [[starwars:Non-human|alien]] populations came to need food for their expanding numbers; as fertile land was converted into farms, herds of these beasts would be captured in the wild and domesticated, while others would be taken from Harakoan tribes and vice-versa. These disputes continue in the modern day, though they have been largely reduced by the [[Treaty of Menat Ombo]], which has proportionally increased the amount of legal trade in their meat and leathers, as well as the animals themselves. | | The arrival of colonists from other worlds would further complicate matters, as the settling [[starwars:Human|Human]] and [[starwars:Non-human|alien]] populations came to need food for their expanding numbers; as fertile land was converted into farms, herds of these beasts would be captured in the wild and domesticated, while others would be taken from Harakoan tribes and vice-versa. These disputes continue in the modern day, though they have been largely reduced by the [[Treaty of Menat Ombo]], which has proportionally increased the amount of legal trade in their meat and leathers, as well as the animals themselves. |

|

| |

|

| Line 50: |

Line 51: |

|

| |

|

| Domestic Histya are gentle, docile beasts, the product of rigorous breeding and training by Harakoans. The vast majority of males in a herd castrated to help keep testosterone levels down among them, while the animals are trained not to fear noise or fire and are led through gentle, peaceful lives of easy food and slow-paced wandering. This produces an animal that is easygoing and obedient, though it also makes wandering stragglers easy prey for wandering Fullasi and other predators. | | Domestic Histya are gentle, docile beasts, the product of rigorous breeding and training by Harakoans. The vast majority of males in a herd castrated to help keep testosterone levels down among them, while the animals are trained not to fear noise or fire and are led through gentle, peaceful lives of easy food and slow-paced wandering. This produces an animal that is easygoing and obedient, though it also makes wandering stragglers easy prey for wandering Fullasi and other predators. |

| | [[File:HistyaTuktuk2.jpg|thumb|right|250px|The Tuktuk, an arctic Histya subspecies, is utilized by New Tython's few arctic tribes for leather, meat, and as a beast of burden.]] |

|

| |

|

| ===Wild and Feral Behavior=== | | ===Wild and Feral Behavior=== |

|

| Histya

|

|

Mammal

|

|

Domesticated

|

|

New Tython

|

|

5-7 years

|

|

1.8 meters

|

|

2 meters

|

|

Gray

|

|

Brown

|

|

Black

|

- Herd animal

- Beast of burden

- Religious sacrifice

|

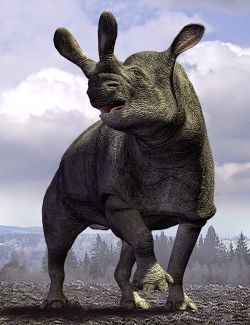

The Histya, also known as a Tuktuk or Banuu in some regions and a Tythonian Herdbeast by colonists, is a quadrupedal herbivore indigenous to the planet New Tython. Found in several subspecies on multiple continents and rugged enough to survive most climates, they are one of the primary beasts of burden for Harakoan villagers and are often kept as livestock. Wild and feral herds also exist, and are hunted by several Harakoan tribes as well as colonist hunters and ranchers.

Evolution and History

The Histya and its ancestors date back millions of years, and have seen their evolution and spread across New Tython mirrored by that of Harakoans and their early Harakonid ancestors. A rugged creature, they ascended from smaller, more mobile quadrupeds before migrating across the surface of Harakoa following an ice age on the planet.

As the world's glaciers and ice bridges retreated, trapping several of the animals in isolated populations on different continents, they would largely adapt to their different surroundings with only a few fringe groups maintaining their arctic adaptations and size to cope with extreme cold. As time went on, they would become domesticated by many tribes as herd or pack animals, while remaining wild populations would roam and be hunted by other Harakoans, as well as predators such as the Fullasi.

Over time, different tribes would put them to different uses, some keeping them as simple livestock while others built nomadic lifestyles around their ability to pack hundreds of pounds of supplies over anything but desert terrain; many, such as the Iwu Gioki, would incorporate them as religious sacrifices, practices that continue in the modern day.

A herd of Histyas grazing in the forests of Kamuekiko.

A herd of Histyas grazing in the forests of Kamuekiko.

The arrival of colonists from other worlds would further complicate matters, as the settling Human and alien populations came to need food for their expanding numbers; as fertile land was converted into farms, herds of these beasts would be captured in the wild and domesticated, while others would be taken from Harakoan tribes and vice-versa. These disputes continue in the modern day, though they have been largely reduced by the Treaty of Menat Ombo, which has proportionally increased the amount of legal trade in their meat and leathers, as well as the animals themselves.

Biology and Description

Histya typically grow to be nearly two meters tall, and can grow to be six feet long and five feet long through the shoulders. Their gray skin grows a thin coating of brown fur, while their adults sport two-pronged, blunt horns from their heads; these are not typically used for more than the odd charge, and are instead digging and scraping tools for the animals to obtain nutrition from the ground or from trees. They have broad shoulders and hips, squat, powerful legs that end in wide feet, and short tails mostly used to swat at insects and signal mates.

Wild populations of Histya tend to be more alert, though only large males defending their herds are ever truly aggressive, and tend to weigh around fifteen hundred pounds; these are much more mobile, and will typically roam across New Tython in herds that run at around forty miles per hour. By contrast, most domestic Histya weigh closer to two thousand pounds and are far more docile than their roaming kin. Pack animals tend to be more muscular and lean, while livestock tend more toward fat and overall size.

One notable exception to this species is the Banuu, a subspecies found on Milil'ea that is typically smaller, weighing at most a thousand pounds and travelling in smaller, faster herds. These are almost exclusively hunted, and can be identified by their thicker, full-body fur, mottled dark brown and black in variations that range from favoring one or the other up to the entire animal being coated in one or the other. Banuu Histya have larger, wider horns, used more frequently as bashing defense against predators and hunters; these are prized as trophies and are often used to make clubs.

The other subspecies of Histya, which remains far closer to its ice age ancestors, is the Tuktuk; found in arctic climes on Milil'ea and southern Kamuekiko, these beasts travel in small herds that constantly migrate the tundra. Their horns are larger and sharper, and are typically used to dig through snow and penetrate ice in search of food or water. Coated in thick, shaggy white fur and weighing in at around two thousand to twenty-five hundred pounds, these large animals are almost always on the move and have become omnivorous scavengers as necessary to survive.

Though all three subspecies vary, they remain close enough in evolution to interbreed, and thoroughbred Histya are actually quite sought-after by Tythonians. While they are quite versatile, one biome they cannot survive in is the desert, with desert-dwelling tribes relying instead upon various reptilians and Korupaka to act as beasts of burden. Histya travelling in desert convoys do still see service due to their immense strength to bear loads, but must be given large quantities of water to survive such a trip and usually emerge emaciated and weak.

Behavior

Domestic Behavior

Domestic Histya are gentle, docile beasts, the product of rigorous breeding and training by Harakoans. The vast majority of males in a herd castrated to help keep testosterone levels down among them, while the animals are trained not to fear noise or fire and are led through gentle, peaceful lives of easy food and slow-paced wandering. This produces an animal that is easygoing and obedient, though it also makes wandering stragglers easy prey for wandering Fullasi and other predators.

The Tuktuk, an arctic Histya subspecies, is utilized by New Tython's few arctic tribes for leather, meat, and as a beast of burden.

The Tuktuk, an arctic Histya subspecies, is utilized by New Tython's few arctic tribes for leather, meat, and as a beast of burden.

Wild and Feral Behavior

Histya in the wild, as well as escaped or lost animals who go feral and integrate with wild packs, move about in patterns that follow the regrowth of grazing land and plant life. They are conscious of weather, though in prime migration season their herds can stretch across grasslands in Owyhyee and can be seen for miles. In Kamuekiko, they are much less widespread and far more careful, as the jungles possess far more predators than open grasslands.

Typically either eating grass or shrubs, Histya will also scrape bark, fungus, and even insect life from trees to supplement their diet; this is in contrast to domestic animals who typically eat a diet of grain. Roaming beasts, they live in a constant cycle of eating, roaming, and mating, interrupted only by predators, hunters, and the change of seasons.

Mating and Social Behavior

As herd animals, male Histya in the wild will often clash in duels during the mating season, as each seeks to mate with as many females as possible. Not all of these matings will result in calves, for females will naturally abort embryos in times of famine or drought, though the ones that do typically survive to adulthood.

Young Histya incorporate with the herd immediately, as they can shakily walk from birth and rapidly grow strong enough to follow. Predators cull off sick and lost young, as well as elderly beasts who wander off at the end of their lives, keeping herds strong. They are social animals and are constantly in contact with one another, forming bonds and sharing food as they rely upon survival by strength in numbers.

By contrast, a typical domestic herd numbers anywhere from six to fifty animals depending on the size of the tribe or farm maintaining it, and will see only a handful of healthy, desirable males able to breed. These will mate with near every female, producing calves that are either undesirable and culled from the herd or desirable and fed well. Naturally this process can lead to problems with inbreeding, though tribes try to trade stock in order to prevent it.

Of particular note are colonist breeding practices, which use interbred subspecies and even gene therapy to produce superior herd and pack animals; these thoroughbreds, typically referred to as Herdbeasts, tend to be larger and stronger than their wild kin and can be quite dangerous if they escape and become feral; thoroughbred males are known to dominate mating in wild herds, thus producing large, voracious, and sometimes more aggressive offspring that can deplete natural food sources and threaten existing populations.

Tribal Politics and Warfare

Histya are kept by many tribes as livestock, and are often traded for their meat and leather, the latter of which is the most common material for Harakoan armor on the planet. That said, these herds present opportunity for war as often as trade, and thieves making off with herds is not uncommon, especially in times of famine. Thus these animals are a central part of Harakoan life.

Interestingly, some tribes deify the beasts as saviors from their gods, viewing fat Histya as omens of divine favor; others, such as the Gioki, offer them up as sacrifices to gods like the Great Father of the Blue Mountains. Colonists and Jedi have been able to exploit these beliefs before, and have used the significance of Histya to both negotiate peace and to swindle unsuspecting tribesmen. As trade has expanded, however, these practices seem to be dying out.